Health literacy is critical to enabling the day-to-day self-management of chronic care. Re-engineering the consumer’s health experience to better address health literacy gaps requires commitment from all stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem.

Close to 36 percent of adult Americans have low health literacy, with significantly higher rates found among lower-income populations. People with low health literacy utilize more health resources compared to those with proficient health literacy, and low health literacy results in an additional $236 billion in U.S. healthcare costs each year.1

What is Health Literacy

Health literacy is the degree to which people can obtain, process and understand health information needed to make good healthy decisions. Deficiencies most often occur when there is a barrier, such as low economic status or a language gap. The National Institutes of Health defines two types of health literacy:

- Personal health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

- Organizational health literacy is the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.2

For example, a gap in health literacy occurs when a patient doesn’t know how to interpret the messaging on their prescription bottle, but also when a clinic fails to create or display appropriate visual aids that may assist persons with disabilities.3

Health Literacy Risk Factors

Due to the dynamic and complex nature of chronic diseases, including the number of doctors and types of interventions managed, people suffering from multiple chronic conditions are some of the most at-risk patients for low health literacy. Decision-making for this kind of patient often occurs daily, making it imperative that multimorbid patients have the competency to self-manage their care.4

In addition to being multimorbid, medically underserved populations, minorities, older adults and low socioeconomic status are all high-risk factors for lower health literacy.5 However, anyone who is unable to understand, process or act on their personal health information is ultimately considered at-risk.

It is estimated that 80 million people in the U.S. are at risk for low health literacy. This number alone signals a problem detrimental to both individuals and healthcare on the whole.

Win-Win Solutions

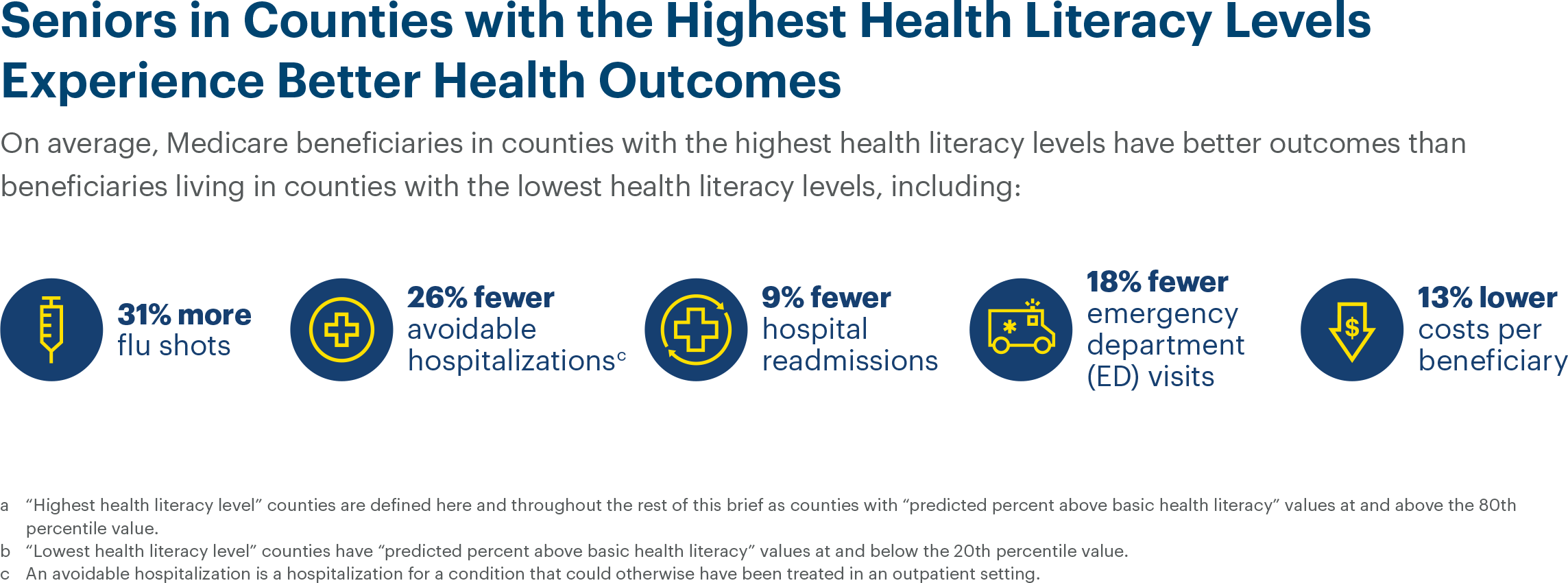

Low health literacy often correlates with poor health outcomes and inadequate use of healthcare services. People classified as having low health literacy are more likely to be hospitalized, not receive preventive care, have low adherence to medication regimens, not heed or understand health messaging, and for certain subgroups, have a much higher mortality rate.6

Increasing health literacy has proven to decrease emergent care and long admission stays, thereby reducing avoidable charges and the patient’s use of auxiliary care.6

Some of the most comprehensive measures of health literacy evaluate individuals on their ability to seek out information, communicate effectively with healthcare providers, navigate systems, and manage their daily care.4 These measures provide a roadmap for facilitating better results, but primarily focus on the behaviors of individual patients. As it is widely accepted that even the most health literate person can be bewildered by an illiterate healthcare system, emerging solutions often include provider settings and social-communal factors.7

The Provider Perspective

One of the limiting factors to improving health literacy, particularly as it relates to the care of multimorbid patients, is the historic mindset of medicine. Medicine has been widely taught and perpetuated in an ‘acute’ mindset that focuses on isolated health events rather than long-term management.8

Medical schools are now shifting their teaching framework to a more holistic approach, broadening their training in topics such as chronic diseases, social determinants of health and health literacy. This shift will take time and there is much work that can be done in clinics and other care settings right now to bolster health literacy and combat outdated practices.

Health systems of all kinds can develop an environment that supports health literacy holistically. From “culturally appropriate educational aids” to interpersonal support groups to innovative uses of technology, there is much that can be done on every level of staffing to better support patients.7 Behind the scenes, collaboration among organizations and better referral systems can also play a significant role in educating and assisting patients in managing their own care.4

Pharmacy Settings

The pharmacy is another setting where issues of health literacy are often obvious. People with low health literacy are at, “higher risk of misinterpreting prescription label instructions, dosage, duration, frequency, warning labels, written information and verbal pharmacist counseling.” In a review of over 47 published studies, communication aids, personalization, and accessible information tools were identified as the top variables in increasing knowledge and adherence in at-risk populations.8

A Need for Methodology

Lastly, methodology for addressing health literacy one-on-one varies greatly from physician to physician. The root cause may stem from a dearth of standard practices for communicating about chronic disease as well as communicating with cultural sensitivity. As such, patients with multiple doctors are likely to experience different approaches from each provider, which can lead to conflicting information that only exacerbates health literacy issues. These cases require a central communicator, often a primary care provider, that will play a pivotal role in coordinating the flow of information to the patient.9

The Social Quotient

Patients don’t typically make health decisions in a vacuum. They often rely on social-communal sources to interpret health information and manage their long-term needs.

When considering how a patient is getting their information, the internet, friends, family, caregivers, social groups and media all play a role in shaping a person’s understanding of their conditions as well as providing crucial support. Systems and providers can use these non-professional influences to their advantage, such as adopting peer-to-peer education and group care programs or intelligent uses of social media to reach their patients in a space they may find more relatable.7

Health systems can work closely with family and caregivers to ensure their health literacy needs are also being met. Caregivers are just as much on the front line of decision-making as the patient themself and may also suffer from low health literacy. This type of outreach requires a community mindset that sees the nexus of disease management in a social environment rather than a clinical one.7

Technology’s Role in Health Literacy

In the era of smartphones, it has become easier than ever to use technology to bridge medicine to the individual – and it can be done daily. Rather than thinking of technology as a passive tool for data collection, it can now be used as a form of patient-centric engagement for helping address chronic conditions, cross language barriers, reach the underserved and empower healthier living.9

Digital solutions show promise as a way to reach individuals with important health information in a strategic, organized and cost-effective way,10 yet there are cautions. As healthcare reaches deeper into technology’s capabilities to engage with patients, careful consideration of how information is presented in a digital format is crucial to the success of the solution.

References

1. J. Vernon, A. Trujillo, S. Rosenbaum, and B. DeBuono. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. University of Connecticut, 2007.

2. National Institutes of Health. Health Literacy. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Published May 8, 2015. https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/health-literacy

3. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health Literacy | Healthy People 2020. Healthypeople.gov. Published 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/health-literacy

4. Muscat DM, Song W, Cvejic E, Ting JHC, Medlin J, Nutbeam D. The Impact of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program on Health Literacy: A Pre-Post Study Using a Multi-Dimensional Health Literacy Instrument. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;17(1):58. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010058

5. Health Resources & Services Administration. Health Literacy | Official web site of the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. Hrsa.gov. Published March 31, 2017. https://www.hrsa.gov/about/organization/bureaus/ohe/health-literacy/index.html

6. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155(2):97. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

7. Poureslami I, Nimmon L, Rootman I, Fitzgerald MJ. Health literacy and chronic disease management: drawing from expert knowledge to set an agenda. Health Promotion International. 2016;32(4):daw003. doi:10.1093/heapro/daw003

8. Wali H, Hudani Z, Wali S, Mercer K, Grindrod K. A systematic review of interventions to improve medication information for low health literate populations. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2016;12(6):830-864. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.12.001

9. Robbins D, Dunn P. Digital health literacy in a person-centric world. International Journal of Cardiology. 2019;290:154-155. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.05.033

10. Zagarella RM, Farrelly FA. ABC Epatite Web App: raising health awareness in a mobile world. mHealth. 2021;0. doi:10.21037/mhealth-20-158

Backed by science and built for engagement, HealthPrize combines behavioral economics, education and gamification to create an enjoyable digital health experience proven to inspire health outcomes that last.